IN THIS ISSUE...

SPRING 2020 VOLUME 66 NUMBER 1

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Bartram’s Garden: a legacy of Colonial

American botany....p.16

BSA student reps share opportuni-

ties for students.... p. 38

BSA President Linda Watson

on graduate education in the

21st century.... p. 3

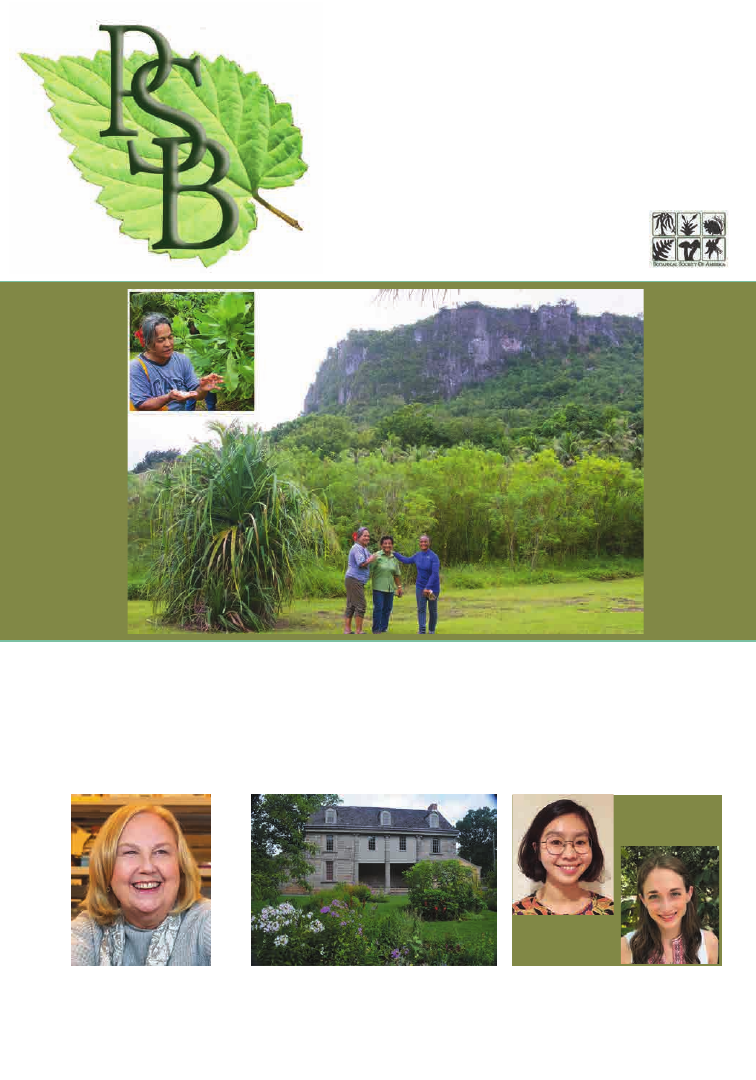

Workshops Advocating Traditional Ecological

Knowledge at the Legislature in Guåhan

Spring 2020 Volume 66 Number 1

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 66

From the Editor

Greetings,

Welcome to 2020! As we kick off a new year, a new

decade, and a new PSB editorial term, I am pleased

to share my thoughts on the future of Plant Science

Bulletin on page 13 of this issue.

As you may know, every issue of Plant Science Bul-

letin can be found on our website https://botany.

org/PlantScienceBulletin/issues.php. While look-

ing through the issues from 1970, I was especially

struck by Arthur Galston’s Address of the Retiring

BSA President, from which I have included an

excerpt in the “From the Archives” section. His

words about the role of plant scientists in world af-

fairs seem especially timely today, and I encourage

you to read his remarks in full at https://botany.

org/PlantScienceBulletin/psb-1970-16-1.php.

The goal of PSB is to keep a record of the important

issues facing botanists, and we continue the tra-

dition of publishing articles developed out of the

lecture given by each BSA President. In this issue,

you can find Linda Watson’s remarks from Botany

2019 on the effectiveness of graduate education for

training students for 21

st

Century careers. This is a

must read for anyone who is training students. Fur-

ther, in the Policy Section, you will find the report

of the 2019 Botanical Advocacy Leadership Grant,

Else Demeulenaere, on her work with the legis-

lature of Guåhan (Guam). Moving back in time,

from the 21

st

to the 18

th

Century, Marsh Sundberg’s

article discusses the history of Bartram’s garden

and its place in the context of Colonial and Early

America. These articles remind us that there are

many ways to effect change in the world. It is safe

to say that botany and botanists have always played

an important role in the public sphere.

Shannon Fehlberg

( 2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin

Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

Seana K. Walsh

(2023)

National Tropical Botanical

Garden

Kalāheo, HI 96741

swalsh@ntbg.org

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Is Graduate Education Keeping Pace with the Dynamic Nature of 21st Century

STEM Careers? - Remarks from Botany 2019 by President Linda Watson ................ 3

Public Policy Quarterly: Workshops Advocate Traditional Ecological Knowledge

at the Legislature in Guåhan .................................................................................................................... 9

Plant Science Bulletin

: A Vision for 2020 ..................................................................................................... 13

SPECIAL FEATURES

Bartram’s Garden: A Legacy of Colonial American Botany .............................................................. 16

SCIENCE EDUCATION

How do BSA members assist or direct people interested in plant careers? ......................... 34

STUDENT SECTION

Update on Botany Conference, Student Opportunities, and More! .............................................. 38

ANNOUNCEMENTS

In Memoriam - Robert B. Kaul ............................................................................................................................ 40

In Memoriam - Michael S. Kinney ..................................................................................................................... 42

In Memoriam - Lee W. Lenz ................................................................................................................................. 43

BOOK REVIEWS

..................................................................................................................................................

45

July 27 - 31

PSB 66 (1) 2020

2

Special Notice Regarding the

Plant Science Bulletin

The articles in this issue of Plant Science Bulletin were written and

prepared in early 2020---just as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across

the planet. In an effort to control the spread of the virus, universities

and institutions were forced to quickly adapt to a world of stay-at-home

orders, disrupting the teaching, learning, research projects, and even

occupations of countless students and members of our community.

The next issue of the PSB will look into the effects of the pandemic on

our members---the adaptation of online teaching and learning, concerns

and opportunities for the near future, and expectations for the 2020-2021

school year. Stay tuned to the BSA social media feeds on Facebook and

Twitter, as well as the PSB home page, for more information on the issue

this summer.

3

SOCIETY NEWS

With the career landscape for Ph.D.s

continuing to shift away from academia,

students and universities alike are asking

if the current model of graduate training is

sufficient to meet the needs and demands

for a workforce in the private sector and in

government agencies. While STEM doctorates

have been trained to have extensive technical

and critical thinking skills and they acquire a

deep and broad knowledge of their discipline,

to what extent are these skills transferable

and are their professional skills sufficiently

broad to successfully pursue careers outside of

academia? The foci of this paper are to explore

the: (1) educational pathways to the primary

employment sectors that biologists generally

pursue, (2) data available on the relative

effectiveness of what may be labeled as the

Is Graduate Education Keeping

Pace with the Dynamic Nature of

21st Century STEM Careers?

By Linda E. Watson

Department of Plant Biology,

Ecology, and Evolution

Oklahoma State University

Stillwater, OK 74074

E-mail: linda.watson10@

okstate.edu

traditional model in STEM under which most

doctoral students are trained, and (3) relevant

training and career resources available to

faculty and students, respectively. This paper is

not a detailed review of careers or professions

in plant biology; instead, the goal is to raise

awareness of the complex issues that students

and faculty may face in understanding the

various dimensions of skills needed for a

diverse array of careers.

21

ST

CENTURY CAREER

PATHWAYS

To better understand the employment

trajectories of U.S. biology doctorates in

general, the American Society for Cell Biology

compiled data from several sources (Polka,

2014 and references therein; https://

www.ascb.org/careers/where-will-a-

biology-phd-take-you/) and generated the

following statistics that serve to illustrate

the most prevalent career pathways. On

average in the United States, a Ph.D. in any

subdiscipline of biology requires seven

years to complete, and only 1 in 12 of these

graduates (8%) obtains a tenure-track

Remarks from Botany 2019 by President-elect Linda Watson

PSB 66 (1) 2020

4

position in academia—rendering tenure-

track faculty positions the alternative career

path. Yet greater than 50% of biology doctoral

students have academia as their career goal.

Of the 63% of doctoral biology students

who complete their degrees, 70% accept

postdoctoral research positions, which

average four years in length with most

doctorates completing more than one postdoc

experience. Of these postdocs, approximately

15% ultimately obtain a tenure-track faculty

position. The remaining 85% of these postdocs

primarily obtain research positions in industry

and government, and to a lesser extent in non-

research, science-related jobs. Of the 30% of

biology doctorates who do not work and train

as a postdoc, approximately 20% obtain non-

tenure track positions in academia, and the

remainder secure research or non-research

positions or science-related jobs outside of

academia. These data (Polka 2014) clearly

illustrate that completing a postdoc is critical

to obtaining an academic position on the

tenure track; however, these summary data do

not account for the occasional individual who

successfully moved directly from a graduate

program into a tenure-track position or for

differences in types of U.S. institutions of higher

education (e.g., top-tier research universities,

primarily undergraduate institutions). The

data also show that getting into industry and

government research positions is possible

with or without completing a postdoc;

however, these data do not parse out the level

of position the Ph.D. was hired into at the

outset (e.g., principal investigator, lab director,

technician). These data, combined with a

recent paper (Langin, 2019) that reports for

the first time that the private sector is now

employing more biology doctorates than

education, underscores the growing need for

carefully training students for careers outside

of academia, since this is where 90% of biology

doctorates find employment.

A survey by the American Association of

Plant Biologists (ASPB) was conducted to

specifically understand career goals of plant

scientists (Binder, 2015 and references therein;

https://blog.aspb.org/plant-science-careers-

survey-summary-and-infographic/). These

survey data are similar to those for biology

doctorates (Polka, 2014) in that approximately

50% of entering plant biology graduate

students have a professional goal of obtaining

a tenure-track faculty position at a top-tier

research university, but only 25% report

obtaining one (this figure is reported for at all

career levels across generations and cohorts,

so is not representative for recent doctorates).

Careers forged outside of academia that were

reported in this survey included government

(37%) and industry research (25%), as well as

non-profits (10%), science publishing (9%)

and government policy (6%); the remaining

10% to 12% reported jobs in a variety of non-

science careers. Approximately 200 of the

800+ respondents for this survey were from

the United States and included the primary

specialties of the ASPB membership such as

plant physiology, cell and molecular biology,

genetics, and genomics, but also included

a small subsample from plant systematics,

ecology, and evolutionary biology. Because the

Botanical Society of America (BSA) includes a

larger proportion of the latter subset of plant

biologists, it is difficult to draw meaningful

conclusions for the entire BSA membership.

Because Ph.D.s are research degrees, it is

not surprising that the majority of STEM

doctorates pursue and obtain positions outside

of academia in research, rather than in science

publishing and government policy. This is

true for biologists in general (Polka, 2014

and references therein) and plant biologists

specifically (Binder, 2015 and references

therein).

PSB 66 (1) 2020

5

EFFECTIVENESS OF

GRADUATE TRAINING IN

RESEARCH

In a study of gainfully employed STEM

doctorates, Kuo and You (2017) explored

three skillsets required to be a successful

researcher as tenure-track faculty vs. those

in government, private industry, and in non-

tenure track positions at universities. These

skillsets included Technical, Interpersonal,

and Communication Skills. To assess the

alignment between graduate training and

job preparation in research, these authors

surveyed 3000 employees to determine which

skills they felt they needed to perform well

for their jobs and which of those skills they

obtained while in their Ph.D. program.

Technical Skills assessed in the survey

included analyzing data, interpreting

information, discipline specific knowledge,

creative and innovative thinking, and quick

learning. Their results indicated that the

non-academic researchers felt they acquired

adequate proficiency in all five skillsets, while

the tenure-track researchers felt they did for all

skills except creative and innovative thinking

and ability to learn quickly.

The Interpersonal Skills assessed in this survey

included oral and written communication,

teamwork, people management, and working

with people outside of the organization.

Ironically, the tenure-track faculty felt

they needed additional training for all

interpersonal skills assessed, while the

researchers in industry, government, and

those not on the tenure track felt they received

adequate training in both written and oral

communication, but needed more training in

teamwork, people management, and working

with people outside of the organization.

For Day-to-Day Skills, all researchers felt they

needed more training in project management,

team management, vision and goal setting,

and career planning and awareness, and to a

lesser extent, decision making and problem

solving. In contrast to a widely held view that

faculty tend to mentor students primarily for

tenure-track faculty positions, this study (Kuo

and You, 2017) indicated that faculty advisors

do an excellent job of training and mentoring

doctoral STEM students in both the Technical

and Interpersonal Skills required for research

positions in government, private industry, and

off the tenure track. However, all researchers,

including tenure-track faculty, felt they needed

better Day-to-Day Skillsets. It is important

to note that this study (Kuo and You, 2017)

focused solely on the employees’ perceptions

of the alignment between their skills obtained

in graduate school in STEM fields and those

needed to perform well in their research jobs.

Other studies focused on the employers’ needs

(Council of Graduate Schools, 2012) and asked

what skills they value in their employees, to

which they uniformly responded strong

communication skills in writing, speaking

and presenting, cross-disciplinary and cross-

cultural communications, and project and

personnel management. When considering

STEM-specific deficiencies in job applicants

and employees, employers voiced needs for

employees to have stronger skills in data

analytics, data sciences, statistics, computing

abilities, genetics and genomics, cognitive

computing, and information systems.

There have been few studies that specifically

focused on the skills in the botanical sciences.

One such survey (Sundberg et al., 2011)

examined the perceptions among faculty

advisors, graduate students, and employers in

government and the private sector. From 1500

responses, they found disconnects between

PSB 66 (1) 2020

6

the top ten perceived strengths identified

by students and deficiencies identified by

faculty and potential employers. Graduate

students ranked their written communication

skills as their top strength, whereas faculty

and employers ranked this as their area in

greatest need of improvement. Similar, but

not identically ranked, disconnects were

identified in problem-solving and verbal

communication skills, where either employees

or faculty advisors assessed these areas in

need of improvement while students felt these

were their strengths. This study also assessed

disconnects for skills relevant to some BSA

members, such as knowledge in ecology and

plant identification; students and mentors

specializing in these areas might also consider

these.

CALLS FOR CHANGE

The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS, 2012)

reported that the job market and the interests

and needs of graduate students are among

the primary driving forces behind graduate

programs needing to provide additional

training that goes beyond Technical Skills.

This report lists several recommendations

to develop more effective Professional

Development programs to train students more

broadly that include: (1) engaging employers

to share their expertise with students on

professional practices, and seeking input from

employers on their needs to shape degree and

course content, (2) placing alumni on advisory

boards at the department and graduate

school levels for greater input, (3) providing

multiple means of delivery to students that

may include online and in-person panels

composed of alumni and employees, (4)

integrating relevant skillsets and experiences

with discipline-specific degree requirements

to offer formal credentials (e.g., certificates),

and (5) partnering with units from across

campus to facilitate students obtaining

broader knowledge they may need to meet

their career goals (e.g., business, law, and/

or communications). This CGS report also

reported several challenges to providing

broader graduate training including limited

resources, selection of content and faculty

with that knowledge, lack of student interest

and participation due to the time demands

already placed on them, and, to a lesser extent,

faculty buy-in. However, the CGS report

also pointed out that graduate schools are

making professional development a priority

in response to the job market and student

demand. Toward these goals, the National

Institutes of Health funded 17 institutions

through the BEST: Broadening Experiences

in Scientific Training program http://www.

nihbest.org/about/) that extends educational

experiences through career development

training, professional development, and

experiential learning (e.g., internships,

visiting another lab) so that career tracks may

better envisioned to include administration

and government, law and science policy, and

science communications. These NIH-funded

BEST institutions have developed webinars

and toolkits and made these resources

available to the public online (http://www.

nihbest.org/about/17-research-sites/).

The National Academies of Sciences

(2018) made several recommendations

that include requiring greater transparency

from institutions by publishing graduation

and job placement rates, and rewarding

faculty for excellence in mentoring. One

recommendation in this report was to

decouple graduate programs from faculty

careers, in that graduate students are integral

to faculty research programs, which may or

may not entirely support the student’s training

and ultimate success in their career. Given that

student research at most U.S. institutions is

largely supported by federally funded research

grants, it is hard to envision that this will be

easily implemented or accepted. Another

recommendation made by this NAS report is to

require all institutions to mandate a set of core

PSB 66 (1) 2020

7

scientific and professional competencies that

all Ph.D. STEM graduates must achieve. These

include developing scientific and technological

literacy, conducting original research, and

developing leadership, communication, and

professional competencies.

At a practical level, Lautz et al. (2018)

outlined a model for multi-year curricula to

prepare graduate students for diverse career

pathways in STEM. They suggested three

tiers of professional development that include

a foundational seminar early in the program,

similar to what many graduate programs at the

departmental level currently offer that provide

exposure to some skills vital to the profession

and the resources to navigate career pathways.

They recommend a second tier of professional

development comprised of specializations

that focus on non-science career needs that

could include communications training, and

intensive exposure to business, policy, and/

or law. The third tier is a career capstone

experience that may include an internship

in a non-academic sector, a study-abroad

experience, or a visiting research opportunity

at another institution. This third tier also

includes the application of professional skills

in setting a career path, as well as developing a

professional network.

One of the first steps in successful career

planning is in recognizing one’s value by

taking the time to assess personal skills,

strengths and ideas (Jensen, 2018). This may

be accomplished through an iterative process

in developing an Individual Development

Plan that starts with a detailed self-assessment,

followed by career exploration, goal setting,

and plan implementation. Some graduate

programs are beginning to require students

to develop individual development plans,

in addition to the usual tasks of writing and

defending research proposals, completing

courses and passing comprehensive exams,

and conducting original research that results in

a defensible dissertation. A useful, interactive

tool for creating an individual development

plan can be found at myidp.sciencecareers.org.

SUMMARY

In summary, there are many resources

available to faculty to improve the alignment

of graduate training needed for today’s

graduate students for them to acquire the skills

needed for success in a variety of jobs outside

of academia. These often include professional

development programs at institutions at the

graduate school level, as well as partnering

with units across campus to provide students

with broader training that make them highly

competitive for their careers. In addition,

there are many forums that discuss the gap

between graduate training and expectations

of employers. These include articles and career

forums in publications such as The Chronicle

of Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed, Nature,

and Science. In addition, there are many that

are discipline specific such as Frontiers in

Ecology and the Environment and Plantae.

LITERATURE CITED

Binder, M. 2015. Plant Science Careers:

Survey Summary and Infographic. American

Society of Plant Biologists: ASPB Plant

Science today. https://blog.aspb.org/plant-

science-careers-survey-summary-and-

infographic.

Council of Graduate Schools and Education-

al Testing Service. 2012. Pathways Through

Graduate School and into Careers, Princeton, NJ.

Jensen, D. G. 2018. Three key elements of

a successful job search mindset. Science:

Careers.

https://www.sciencemag.org/ca-

reers/2018/08/three-key-elements-successful-

job-search-mindset

PSB 66 (1) 2020

8

Kuo, M. and J. You. 2017. Explore the skills

that can open career doors after your doctoral

training. Science: Careers. https://www.sci-

encemag.org/careers/2017/11/explore-skills-

can-open-career-doors-after-your-doctoral-

training

Langin, K. 2019. In a first, U.S. private sector

employs nearly as many Ph.D.s as schools do.

Science: Careers. https://www.sciencemag.

org/careers/2019/03/first-us-private-sector-

employs-nearly-many-phds-schools-do

Lautz, L. K., D. H. McCay, C. T. Driscoll, R.

L. Glas, K. M. Gutchess, A. J. Johnson, and G.

D. Millard. 2018. Preparing graduate students

for STEM careers outside academia. Eos

99. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EO101599.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineer-

ing, and Medicine. 2018. Graduate STEM

Education for the 21st Century. Washington,

DC: The National Academies Press. https://

doi.org/10.17226/25038.

Polka, J. 2014. Where will a Biology PhD

Take You? The American Society for Cell

Biology: Careers, Emerging Voices. https://

www.ascb.org/careers/where-will-a-biology-

phd-take-you/

Sundberg, M. D., P. DeAngelis, K. Havens,

K. Holsinger, K. Kennedy, A. T. Kramer, R.

Muir, et al. 2011. Perceptions of strengths

and deficiencies: disconnects between gradu-

ate students and prospective employers. Bio-

Science 61: 133-138.

FROM THE

PSB

ARCHIVES

60 years ago:

“At the end of 1959, George S. Avery, Jr., Harriet B. Creighton, and Paul B. Sears retired from

the Editorial Board of Plant Science Bulletin. They had served on the Board since this publication was founded.

The Botanical Society of America owes these members a debt of gratitude for their devotion and great service to

the Bulletin during the past five years. Three new members were appointed to the Board as of January 1, 1960.

They are Norman H. Boke, Elsie Quarterman, and Erich Steiner.”

“New Editorial Board” PSB 6(1): 2

50 years ago:

“What, in fact, are the ecological consequences of the widespread massive application of

herbicides? With respect to Vietnam, it should be noticed that in 1968 approximately a million and a half acres

of forested land and a quarter of a million acres of crop land were sprayed with an average of about three gallons

per acre (or ca 27 lbs./acre) of chemical. This means that almost fifty million pounds of assorted herbicides were

dumped on the countryside in that one year. Most of this was in the form of the phenoxyacetic acids; some was

in the form of picloram; some, probably about three quarters of a million pounds, in the form of cacodylic acid.

It is frequently alleged that a single spray with a defoliating chemical, such as 2,4-D or 2,4,5-T, produces

no permanent damage to a forested area. This, it seems to me, is a pious hope in view of the paucity of hard data

available and recent observations on mangrove associations indicate extensive kill after one spray.”

[Galston provides several examples of the potential hazards to the environment and human health.]

“We must hope that such chemical warfare, committed in the name of the American people, will never

again be employed. All American citizens, and scientists and botanists in particular, need to concern themselves

with a practice that, in the eyes of some, is outside accepted international law.”

Galston, Arthur W. “Plants, People, and Politics” PSB 16(1): 1-7

PSB 66 (1) 2020

9

Most archipelagoes harbor unique ecosystems

with high floristic and faunistic endemism

that are tightly connected with the culture and

language of indigenous people. Unfortunately,

islands also suffer from increased habitat loss,

high extinction rates, high invasive species

numbers, and threats to traditional practices

and languages. Guåhan (Guam) is the most

southern island of the Mariana Archipelago

in the northwestern Pacific Ocean and home

to approximately 54 endemic terrestrial plant

species (Costion et al., 2012). The island

experienced several waves of colonization,

which forcefully changed the way of life of the

indigenous CHamoru people. In 2015, the U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service listed 15 plant species

under the Endangered Species Act for Guåhan.

One of these, Serianthes nelsonii or Håyun

Lågu, has a single surviving seed-producing

tree in a pristine primary limestone forest in

northern Guåhan and is at risk because of the

military’s plans to construct a firing range.

This critically endangered species also occurs

in the second most southern island of the

archipelago, Rota, but it is uncertain if the Rota

S. nelsonii populations are conspecific with the

tree from Guåhan. For my dissertation, I am

conducting a phylogenetic study on Serianthes

Workshops Advocate Traditional

Ecological Knowledge at the

Legislature in Gu

å

han

By Else Demeulenaere

Associate Director, Center for

Island Sustainability

UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam

E-mail: else@uog.edu

to guide management and to resolve questions

about conspecificity. Although the military

has not planned the removal of the last

Serianthes tree, the proposed buffer zone

around the tree will endanger establishment

of a healthy population and puts the tree

at risk during typhoons. In order to use the

firing range, a large surface danger zone

(SDZ) will reach over most of Litekyan, a

culturally important area below the cliffs

where the tree grows. The SDZ would close

most of Litekyan off to the public and cultural

practitioners. History books list Litekyan as a

place with high quality timber, including the

Håyun Lågu. Adding an ethnobotanical and

policy piece to my dissertation resulted from

my involvement with the social movement to

protect Litekyan. This also sparked my interest

to further look into ethnobotanical uses of

Serianthes in Micronesia and how different

island cultures value this tree.

Thanks to the Advocacy Leadership Grant,

I could organize two public events at the

35th Guåhan legislature in collaboration

with senators: (1) a workshop illustrating

the importance of Traditional Ecological

Knowledge (TEK) of native plant species in

Litekyan, and (2) a native tree-planting event.

The office of Senator Sabina Perez assisted

to organize the workshop at the legislature,

which was live-streamed on their legislative

channel. The coastal vegetation and limestone

forest at Litekyan harbor many plant species

that have remained a valuable resource for

traditional healers (yo’ åmte). These yo’ åmte still

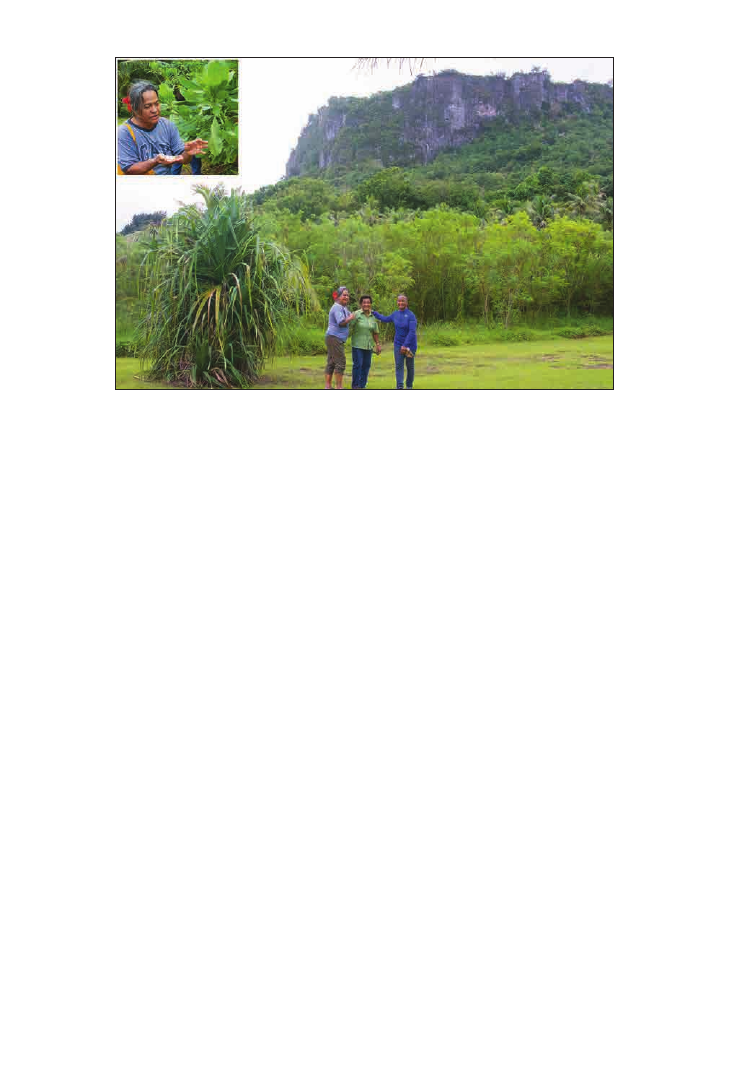

collect åmot (medicine) at Litekyan (Fig. 1). The

PSB 66 (1) 2020

10

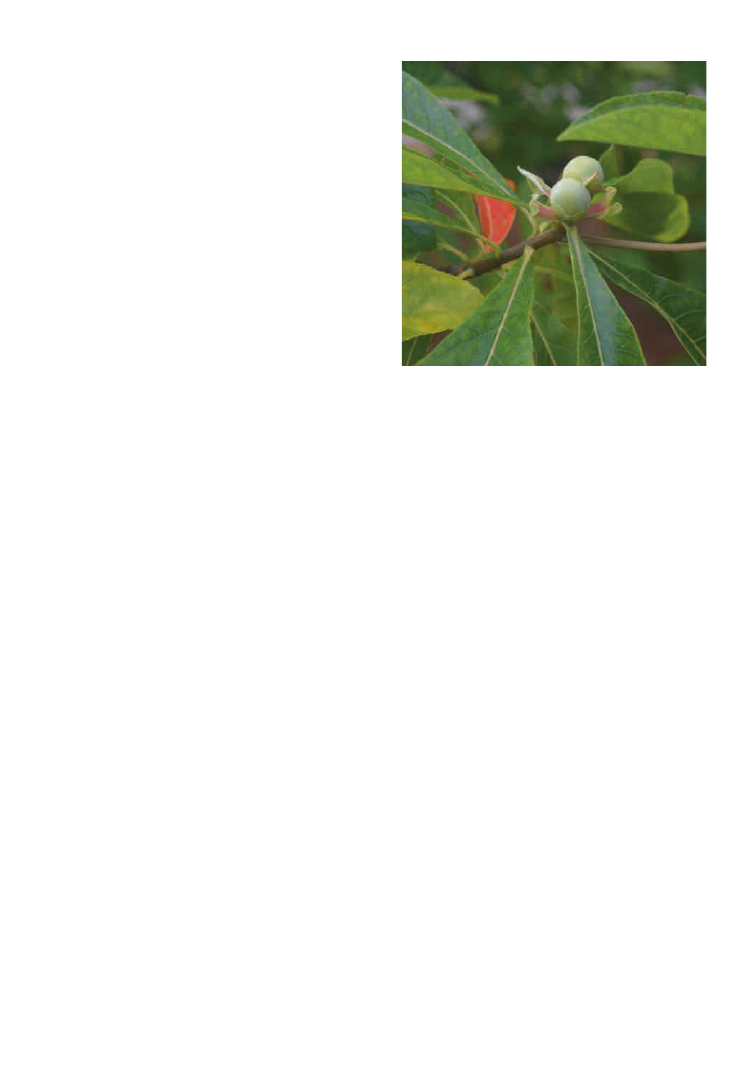

Figure 1. Healers gather to collect åmot (medicine) at Litekyan. In the top left, yo’ åmte Susan is

showing the nanaso fruit, used for eye ailments.

workshop was supported by healers from the

Håya Foundation, who prepared medicinal

teas. With help from the Advocacy Leadership

grant, I designed ethnobotany posters that

illustrate the importance of TEK in Guåhan

and Micronesia. Potted plants and herbarium

specimens were used to illustrate some of the

most common and culturally important plants

(Fig. 2).

For the second event, the offices of Senator

Regine Biscoe Lee and Senator Perez, together

with the Center for Island Sustainability of

the University of Guam, organized a tree-

planting event that put members of the

legislature and the community to work

(Fig. 3). Mr. Joe Quinata from the Guam

Preservation Trust selected an appropriate

location for planting these native trees in the

capital of Guåhan. The trees and shrubs used

during the workshop will create a sheltered

place for the senators to meet outside their

offices and enjoy some of the healing powers

of the native plants used. Senators will be

able to pick gausali flowers (Bikkia tetrandra)

to decorate their hair or use drops of the

juice of nanaso fruits (Scaevola taccada) to

relieve those with dry eyes possibly due to

extensive computer use. The main goals of

the workshops were to stimulate lawmakers

to preserve TEK, endemic plants, and sacred

places by drafting bills that incorporate TEK

into management practices, connecting the

land and the people. Senator Perez said, “It is

imperative that we incorporate the valuable

teachings of our ancestors in our actions and

our policies.” Several newspapers and news

media in Guåhan covered the events, and

social media groups engaged with the topic.

After the events, I followed up with Senator

Perez and Senator Kelly Marsh-Taitano to

discuss legislation to strengthen the protection

of endangered species, ethnobotanical uses,

and sacred places such as Litekyan.

To reach students in local schools in

Micronesia, I have designed and distributed

stickers featuring images of native plants,

accompanied with a phrase in the local

language about their ethnobotanical or

ecological importance (Fig. 4). These stickers

can be used to emphasize hands-on, real-

PSB 66 (1) 2020

11

Amy Lovecraft (UAF), Dr. Sveta Yamin-

Pasternak (UAF), Dr. Kevin Jernigan (UAF),

and Dr. Don Rubinstein (UOG)—for guidance

on my research. Most importantly, I want to

thank all the TEK holders for sharing their

knowledge and to keep these practices alive

for future generations to come. My research is

grounded in learning from indigenous peoples

and recognizes the importance of indigenous

epistemology (Smith, 2012). I hope that by

connecting research and activism with the

visions, aspirations, and needs of indigenous

communities, we can advance cultural

sustainability, social, and political well-being

in the Mariana Islands.

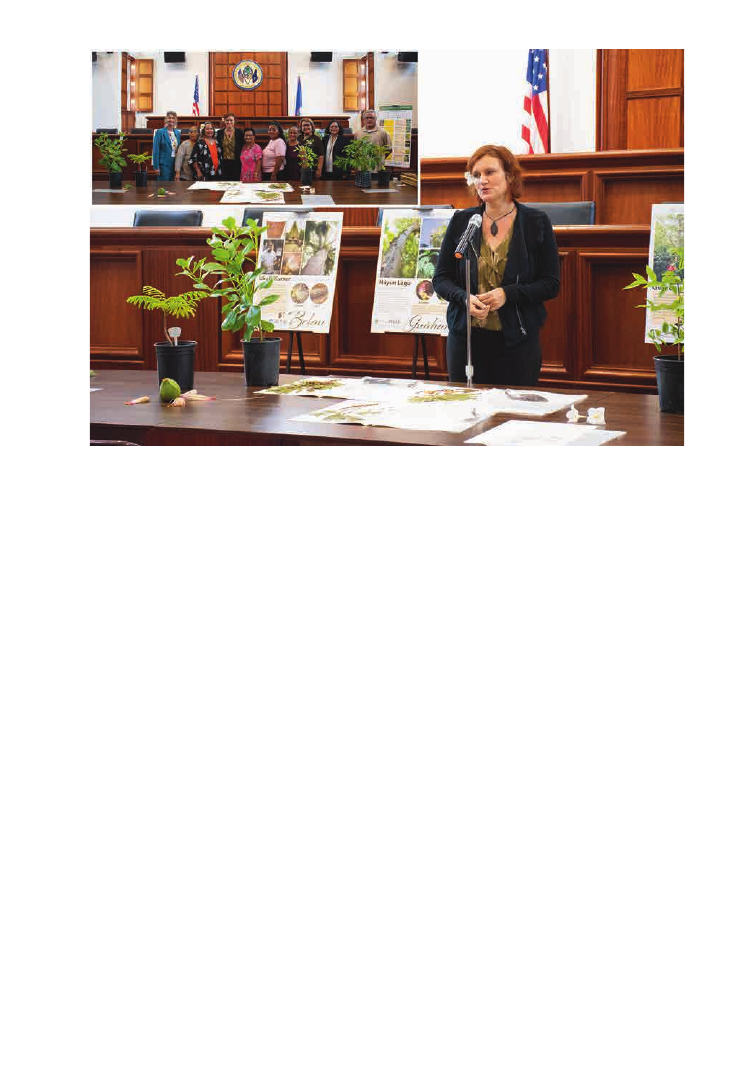

Figure 2. Else Demeulenaere presents during the workshop at the Guam Legislature. The Advo-

cacy Leadership Grant funded outreach posters that will be available online to support place-based

education. The inset picture shows attending senators, yo’ åmte and the chief of Forestry at the

Guam Legislature.

world, place-based learning experiences.

These educational experiences increase

academic achievement, help students develop

stronger ties to their community, enhance

students’ appreciation for the natural world,

and create a heightened commitment to

serving as active, contributing citizens (Ban

et al., 2018; Davidson-Hunt and O’Flaherty,

2007). At the same time the students can use

the stickers to advocate for the protection of

their islands’ biocultural diversity.

I want to thank the Botanical Society

of America and the American Society

of Plant Taxonomists for the Advocacy

Leadership Grant, which helped to facilitate

these conversations, and my dissertation

committee—Dr. Steffi Ickert-Bond (chair,

University of Alaska Fairbanks [UAF]), Dr.

Xiao Wei (University of Guam [UOG]), Dr.

PSB 66 (1) 2020

12

LITERATURE CITED

Ban, N. C., A. Frid, M. Reid, B. Edgar, D. Shaw, and P.

Siwallace. 2018. Incorporate Indigenous perspectives

for impactful research and effective management.

Nature Ecology and Evolution 2:1680–1683.

Costion, C. M., and D. H. Lorence. 2012. The endem-

ic plants of micronesia: a geographical checklist

and commentary. Micronesia 43: 51–100.

Davidson-Hunt, I. J., and R. M. O’Flaherty. 2007. Re-

searchers, indigenous peoples, and place-based

learn-ing communities. Society and Natural

Resources 20: 291–305.

Smith, L. T. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies. Zed

Books. Otago University Press.

Figure 4. Else Demeulenaere hands over

Serianthes nelsonii or tronkon guåfi stickers to

Rota Forester James Manglona.

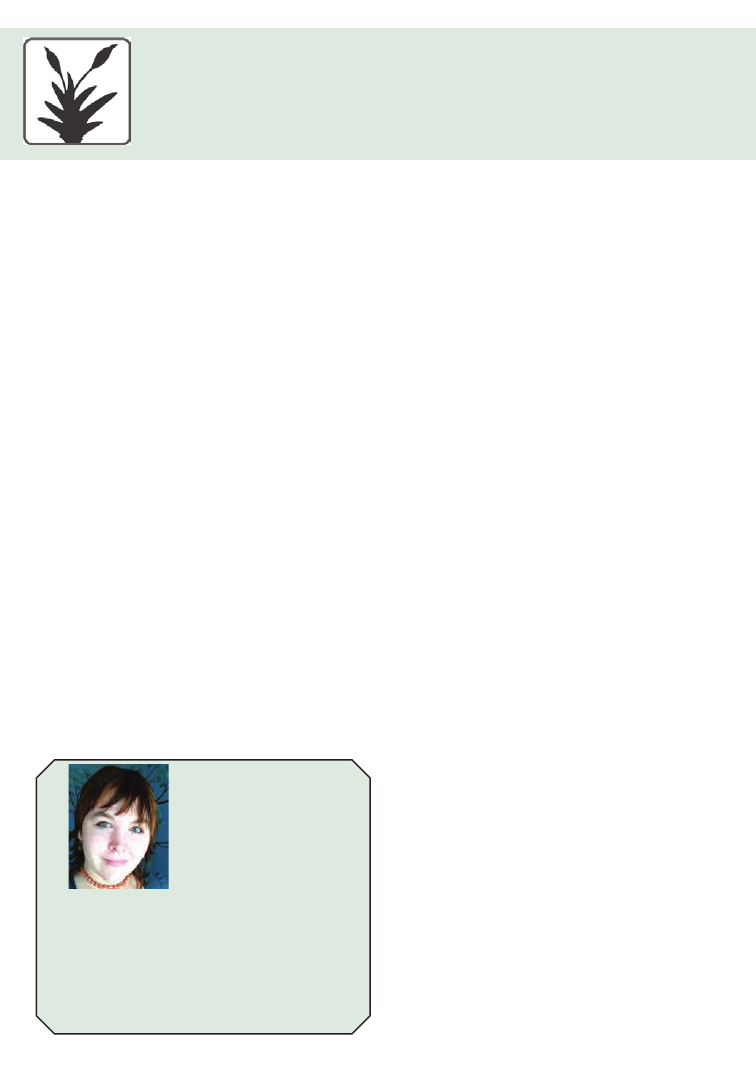

Figure 3. The University of Guam Center for Island Sustainability and senators of the 35th Guam

Legislature at the tree planting ceremony on October 24, 2019 on the lawn outside of the Guam

Congress Building.

PSB 66 (1) 2020

13

With this issue, Plant Science Bulletin is

entering its 65

th

year of publication. Since its

first issue in 1955, the goal of PSB has been

to communicate significant events, facilitate

discussion of the concerns and challenges that

arise in botany as a professional discipline,

and foster community within the plant

sciences. In particular, contributions to PSB

have focused on the intersection of botany

with education, industry, and government, as

well as the professional life of botanists.

I have served as Editor-in-Chief of Plant

Science Bulletin since 2015 and am delighted

to continue this role until 2025. Over the last

five years, my goal has been to ensure that

the content of PSB reflects the interests and

composition of the 21

st

century Botanical

Society of America and that the Bulletin

provides a platform from which to share ideas

and resources.

Since 2015, we have implemented some

exciting changes. We gave PSB a new look

with a new logo and initiated several regular

features, including sections dedicated to

Students and Public Policy. The Student

Representatives and chairs of the Public

Policy Committee have worked tirelessly to

bring you current news and articles of interest

in each issue. We also continued the tradition

Plant Science Bulletin:

A Vision for 2020

of having a dedicated section for Education

News and Notes, which Catrina Adams, the

BSA Education Director, puts together for

each issue. I extend special thanks to all of our

regular contributors.

There have been significant changes to BSA

publishing since 2015, as American Journal

of Botany and Applications in Plant Science

are now officially under the Wiley umbrella.

Plant Science Bulletin, however, continues to

be self-published. This means that production

of PSB requires significant effort by the BSA

staff, but it also gives us the flexibility to

adapt the Bulletin to the needs of the Society.

Although PSB is published in-house, we plan

to take full advantage of Wiley’s publications

platform and Plant Science Bulletin is included

on the new Publications Hub at https://

bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/. I am also

looking forward to working with the new BSA

Social Media Interns to promote PSB articles

to a wider audience and to develop strategies

to make articles, including those from back

issues, easier to access and transmit.

In 2016, Plant Science Bulletin published its

first special issue on Citizen Science and in

the next five years, we hope to publish more

of these on various topics of interest. We are

always working to increase the number and

By Mackenzie Taylor

Editor-in-Chief, PSB

PSB 66 (1) 2020

14

breadth of contributions PSB, and I encourage

you to email me with your ideas. My favorite

thing about being Editor is getting to work

with so many different people who contribute

to botany in so many different ways. The

original idea was for PSB to perform a

“unifying function” among plant scientists

and I feel strongly that this is important.

I am excited to see what the next five years

have in store for PSB. My hope is PSB that

every BSA member will find something of

interest within its pages.

PSB by the Numbers

(2015-2019)

17 issues

14 Peer-Reviewed Articles (Special

Features)

16 Editor-Reviewed Articles

114 Book Reviews

152+ Contributors

PSB 66 (1) 2020

15

T:

+44 (0)1223 839365

@bdspublishing

E:

info@bdspublishing.com

Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing

www.bdspublishing.com

Achieving sustainable

greenhouse cultivation

20%

online or

der d

iscou

nt

Use c

ode B

SA20

BURLEIGH DODDS SERIES IN AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE

Edited by Prof. Leo Marcelis and Dr Ep Heuvelink, Wageningen University,

The Netherlands

Books are available in print and

digital format. Order via our

online bookshop:

www.bdspublishing.com

Quote code BSA20

at checkout to receive 20%

discount

K E Y F E AT U R E S

• Reviews advantages and disadvantages of

greenhouses, net houses, aquaponic and vertical

farming systems.

• Detailed assessment of current research on

optimising the aerial environment and root

development.

• Focus on systems control to optimise product

quality and environmental impact.

20%

online order

discount. Use code

BSA20 at checkout.

N E W R E L E A S E S

16

SPECIAL FEATURES

His garden is a perfect portraiture of himself,

here you meet wt[sic] a row of rare plants

almost covered over wt[sic] weeds, here with

a Beautifull[sic] Shrub, even Luxuriant

Amongst Briars, and in another corner an

Elegant & Lofty tree lost in common thicket

– on our way from town to his house he

carried me to several[sic] rocks & Dens where

he shewed[sic] me some of his rare plants,

which he had brought from the Mountains

&c. In a word he distains to have a garden

less than Pensylvania[sic] & Every den is an

Arbour[sic], Every run of water, a Canal, &

every small level Spot a Parterre, where he

nurses up some of his Idol Flowers & cultivates

his darling productions. —Colden (1754).

Bartram’s Garden: a Legacy of

Colonial American Botany

Bartram’s Garden is recognized as the oldest

botanical garden in North America and one of

the first in the world not established as a physic

garden associated with medical instruction

(Bewell, 2017). As suggested in the quote

above, the garden was, and is, a reflection of

the philosophy of its founder, John Bartram.

In this paper I will briefly review the history

of the Garden and describe its role in the

development of several aspects of American

botany, as a scientific discipline, a commercial

business, and a public educational institution.

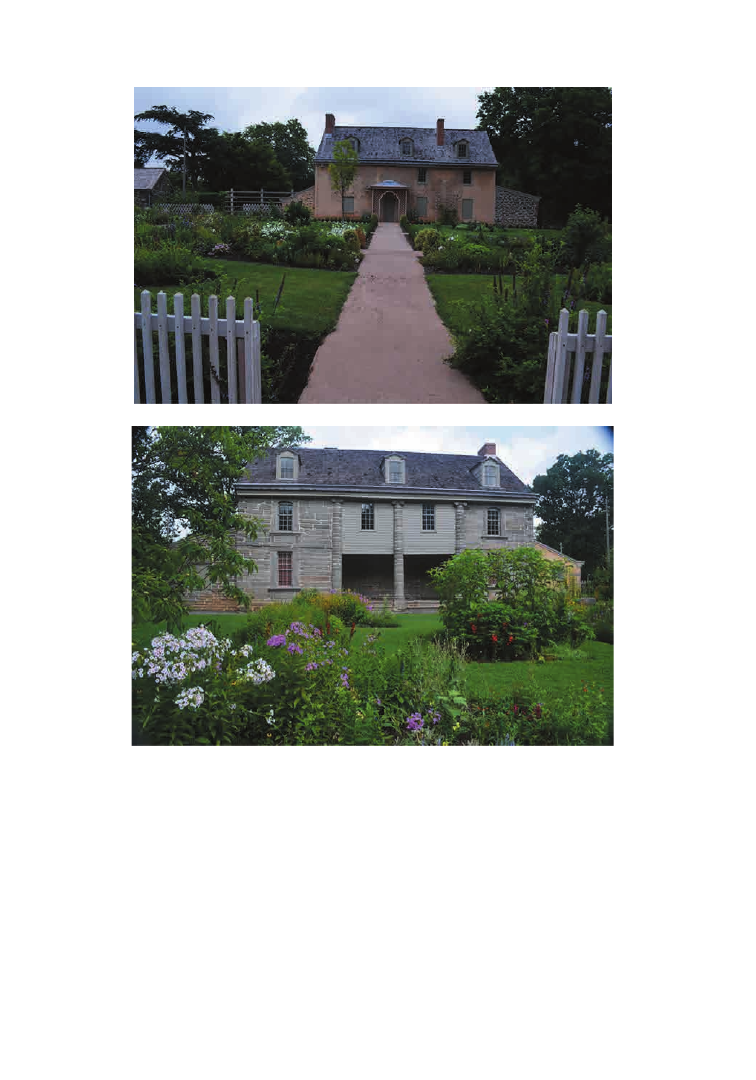

THE SITE

Bartram’s was not the first botanical garden,

even in Philadelphia. In 1718 Dr. Christopher

DeWitt established a medicinal garden in

Philadelphia, and a 1729 poem refers to an

even earlier medicinal garden at Batchelor’s

Hall (Harshberger, 1899). Fry (2004) notes

that Bartram had a small garden collection on

his original farm in Darby between 1723 and

the death of his first wife in 1727. He suggests

that the idea of an even larger garden was

already on Bartram’s mind when he purchased

the original 102 acres (+10.5 acres of marsh)

in Kingsessing Township, about 4 miles

southwest of Philadelphia, from the heirs of

the Swedish colonial plantation, Aronameck,

for £145 (Fry, 2004). (Note: Berkeley and

By Marshall D. Sundberg

Department of Biological

Sciences

Emporia State University

Emporia, KS 66801

msundber@emporia.edu

PSB 66 (1) 2020

17

Berkeley [1982] list the sale as £45 for 112

acres; Meyer [1977] listed the sale as 102

acres.) The deed was purchased at a sheriff’s

sale on 30 September 1728 (Darlington,

1840). Fry (2004) suggests Bartram probably

planted a kitchen garden in 1729. This could

be considered the “first seed” that grew into

Bartram’s Garden, although 1731, the date

on the cornerstone of the stone house, is

generally considered to be the founding date

of the garden (Bartonia, 1931). Subsequently

Bartram made additional purchases so that

the property extended back to the top of the

hills on either side of the original property

(Bartram, 1807).

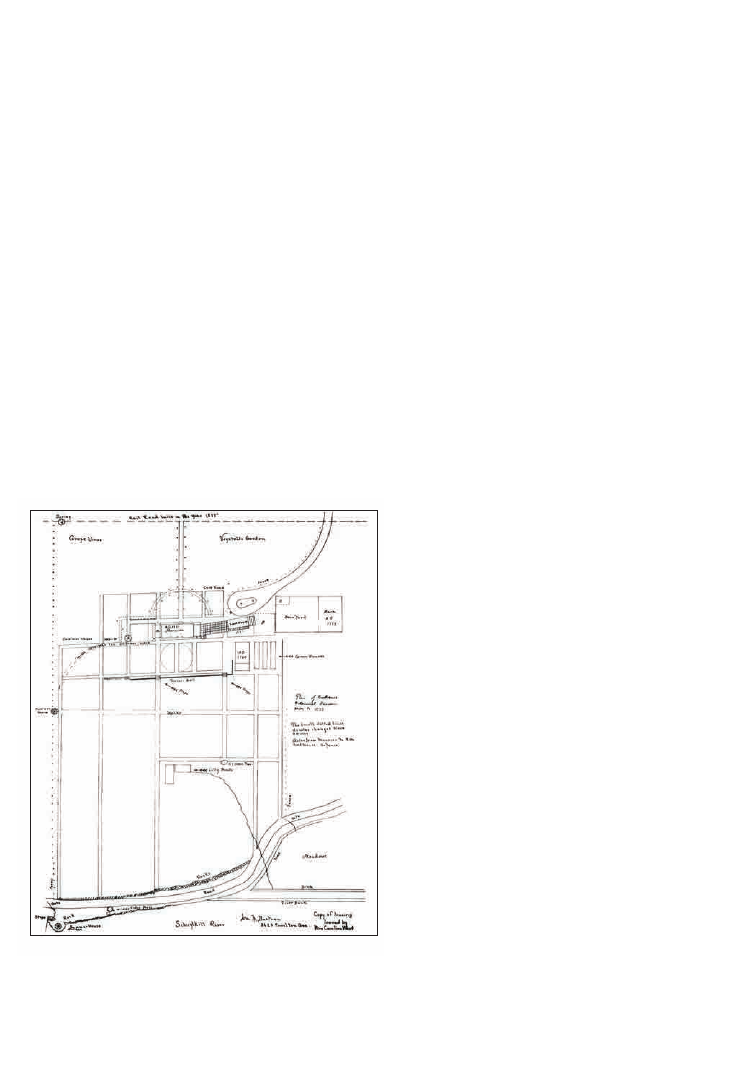

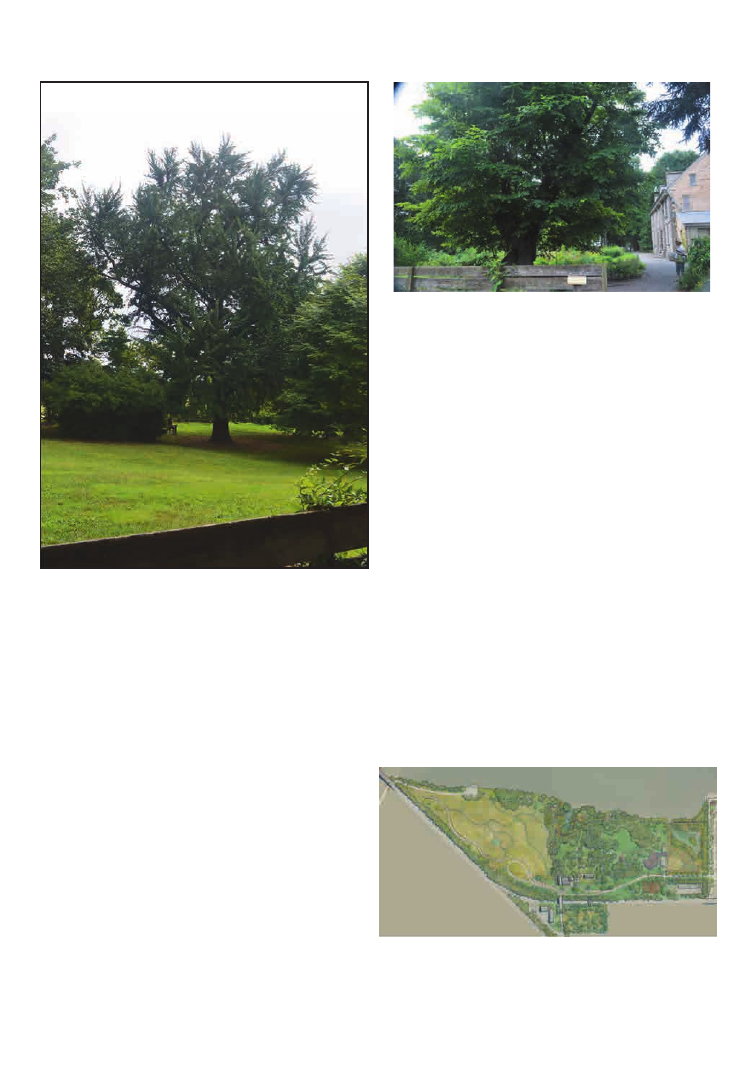

The garden sits on a natural terrace that rises

gradually from the river floodplain toward the

northwest, about 45 feet above the Schuylkill

River. A freshwater spring in the lower garden

was used to cool the milk house and feed a

small freshwater lily pond (Figure 1). There

are a variety of soil types, from sandy and silty

loam to rocky. Recent analyses identify eight

or more distinct soil types on the property

(Fry, 2002). In general, soils around the

house on the upper terrace are well drained

while those from the pond to the river are

more poorly drained clay soils. The variety of

exposures and soil types allowed Bartram to

successfully transplant plants from northern

areas such as upstate New York and southern

areas such as the Carolinas. The original

cultivated garden covered at most five or six

acres, but he subsequently bought additional

acreage so that by 1807, his son William could

note that his father “arranged [his collected

plants] according to their natural soil and

situation, either in the garden, or on his

plantation, which consisted of between 200

and 300 acres of land, the whole of which he

termed his garden (Bartram, 1807; Berkeley

and Berkeley, 1982).

When Bartram purchased the property, it

included a small house and orchard. The

original building became the present hall

and parlor that Bartram incorporated into an

enlarged home (Cheston, 1953; NPS, 2001).

According to Cheston, the white oak beam

above the fireplace dates from 1684, when

the original house was built. Pyle (1880)

suggested that the small closet beside the

parlor fireplace, which extends behind the

chimney, was probably used by Bartram to

keep living specimens in winter and/or to dry

specimens. Tradition says that immediately

upon purchasing the property, Bartram

began quarrying and finishing his own stone

to enlarge the building, which he completed

in 1731 (True, 1931, Figure 1). Indeed, in

January 1757, he wrote to a neighbor, Jared

Eliot, explaining exactly how to hew stones, up

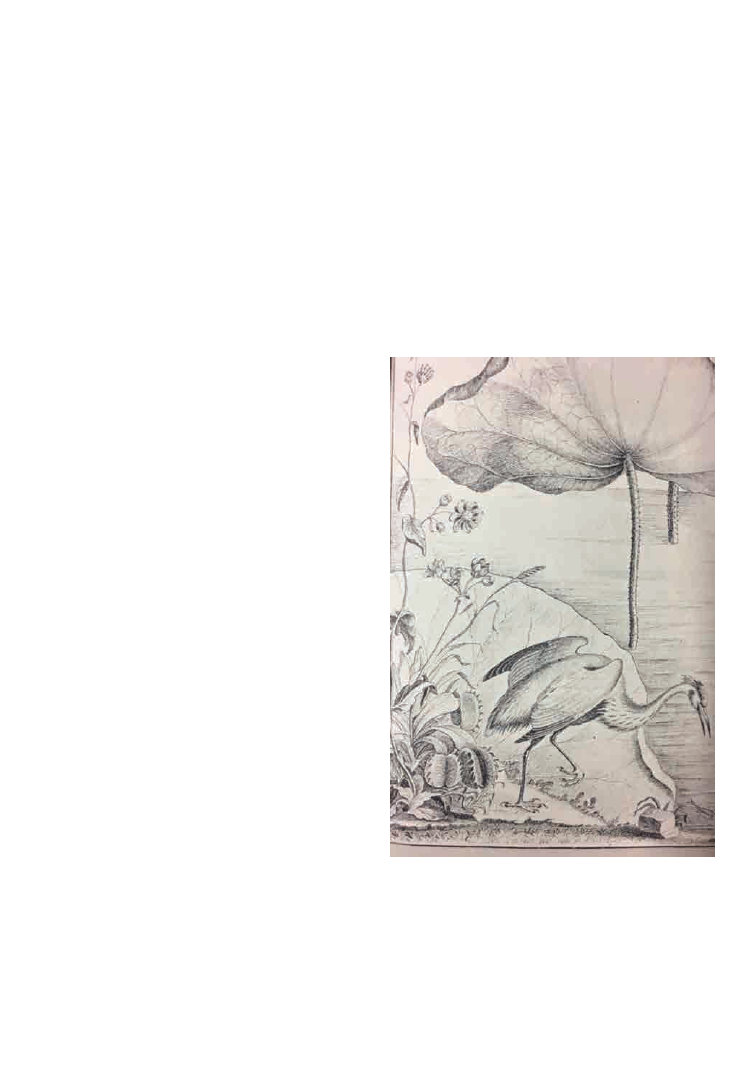

Figure 1. A sketch of John Bartram’s House

and Garden as it appeared before 1777.

(By permission of Joel T. Fry, John Bartram

Association.)

PSB 66 (1) 2020

18

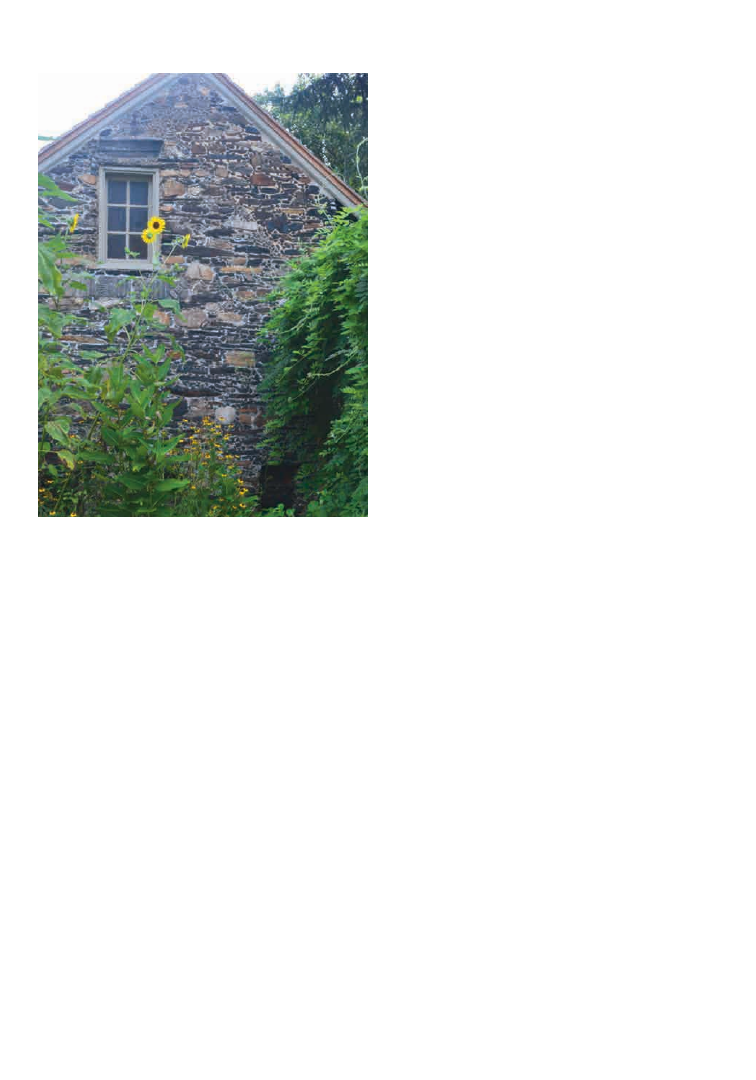

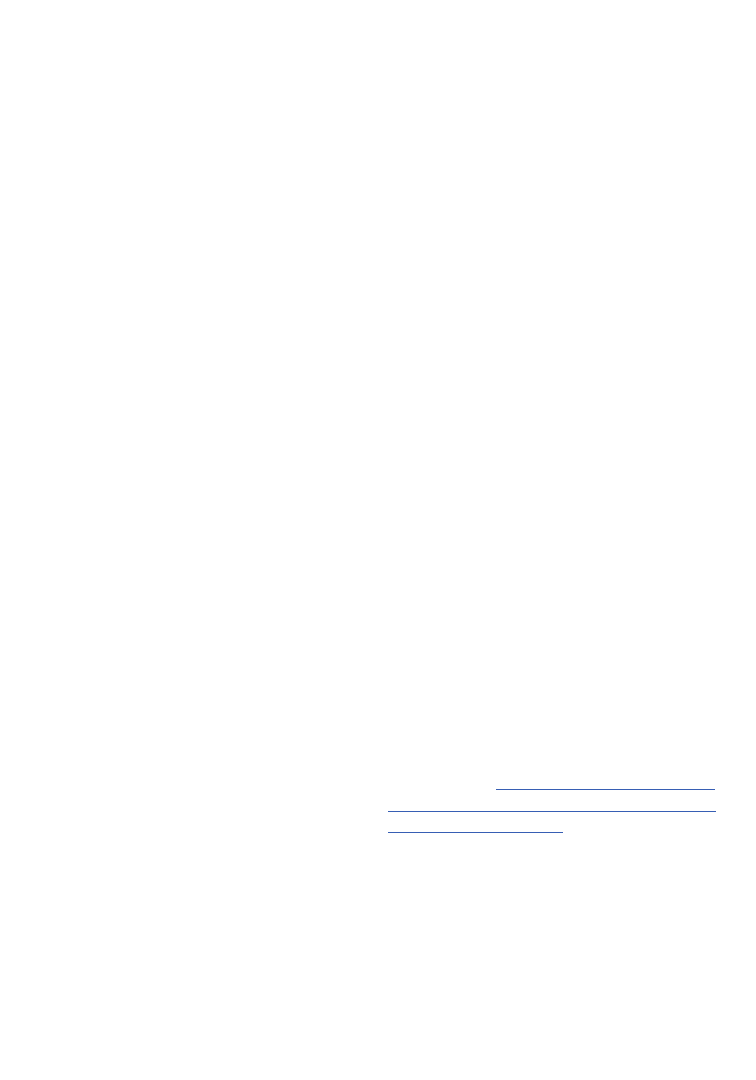

Figure 2. John Bartram’s House today. A, Front view of house from the west. B, Rear view of

house from the east. (author’s images)

A

B

to 17 feet long, using a rock drill and wedges

(Berkeley and Berkeley, 1992). The original

portion of the house was only one room deep,

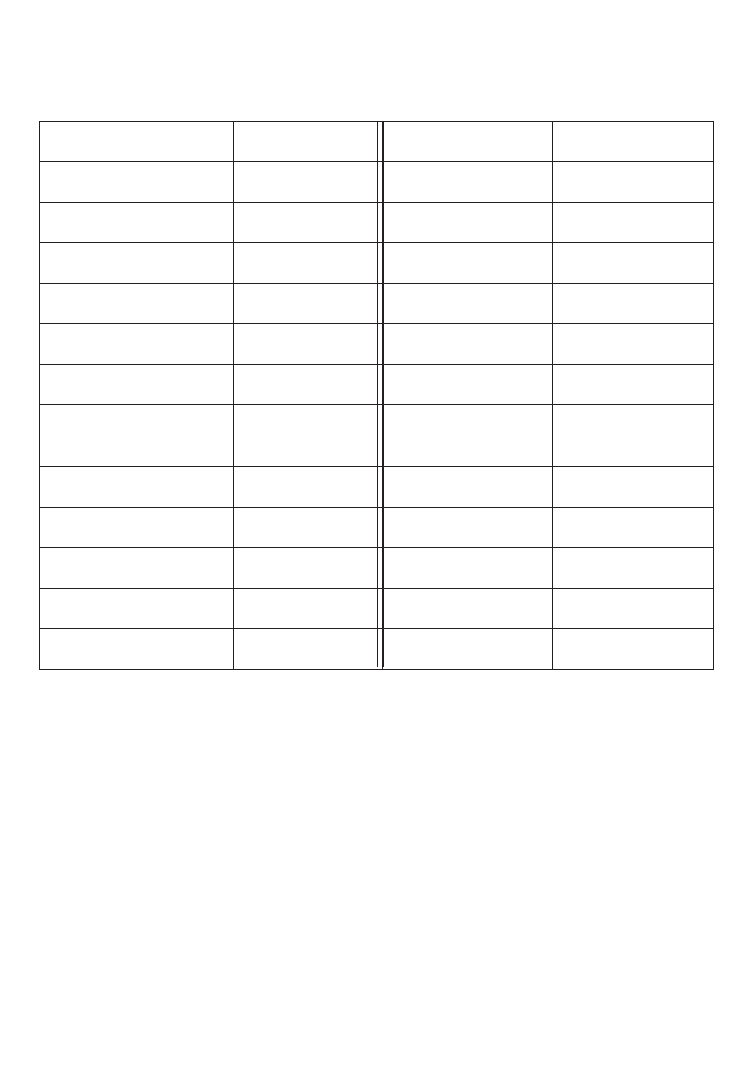

and two stories tall. In 1737 he built an out-

building, the seed house (Figure 1, far left of

Figure 2A, and Figure 3), on the north side

of the main house. In the 1840s he added a

large kitchen on the north side of the house

with a very large hearth on the north wall (see

location of chimney on left side of Figure 2A).

In 1760 Bartram built a free-standing stone

greenhouse with glass walls on the east side

and heated with a Franklin stove (Figure 1;

Fry, 2002). This was despite his letter to Philip

PSB 66 (1) 2020

19

Miller three years earlier: “I don’t greatly like

tender plants what wont[sic] bear our severe

winters but perhaps annual plants that would

perfect their [sic] seed with you without

the help of A hot bed in the spring will do

with us in the open ground” (Berkeley and

Berkeley, 1992). However, in November 1759,

Miller wrote, “With this I send you a parcel

of Bulbous rooted flowers from the Cape of

Good Hope. If they succeed as well with you

as they have done in the Chelsea Garden, I am

sure they will give you pleasure, but I imagine

they will not live thro[sic] the winter without

protection, which is the case here.” This was

probably the stimulus Bartram needed. Seven

months later he wrote to tell Collinson, “Dear

friend I am A going to build A green-house - -

stone is got & hope as soon as harvest is over to

begin to build it to put some pretty flowering

winter shrubs & plants for winters diversion

not to be crowded with orange trees or thos

natural to ye torrid zone but such as will do

being protected from frost…” (Berkeley and

Berkeley, 1992). The greenhouse became

especially important for maintaining some

of the exotic plants that were sent to Bartram

from his correspondents both in Europe and

in the southern United States.

Around 1770 he extended the home both to

the north and east toward the river. On the

first floor were a study and pantry flanking a

porch on the east and a summer kitchen (now

restrooms) on the north. Three new rooms were

added to the second floor on the east and a six-room

third story raised the roof (NPS, 2001). Slaughter

(1996) suggests that this was to provide rooms

on the south side of the house for John and

Mary to retire in while John Jr., and his new

wife, Eliza Howell (m. 1771), would occupy

the north side. The new east façade sported

a distinguishing row of pillars (Figure 2B)

(Cheston, 1953). An additional one-story

room was also added on the south side in

the early 1800s (NPS, 2001). The Franklin

stove, a gift from Benjamin Franklin, is the

only original furnishing in the current house

according to Cheston (1953), but Pyle (1880)

claims the “old Franklin stove in the sitting

room – a present from Benjamin himself, like

enough-has been removed….” According to a

Russian visitor, “His house is small but decent

… I had no sooner entered, than I observed

a coat of arms, in a gilt frame, with the name

of JOHN BERTRAM[sic]” (de Crevecoeur,

1782).

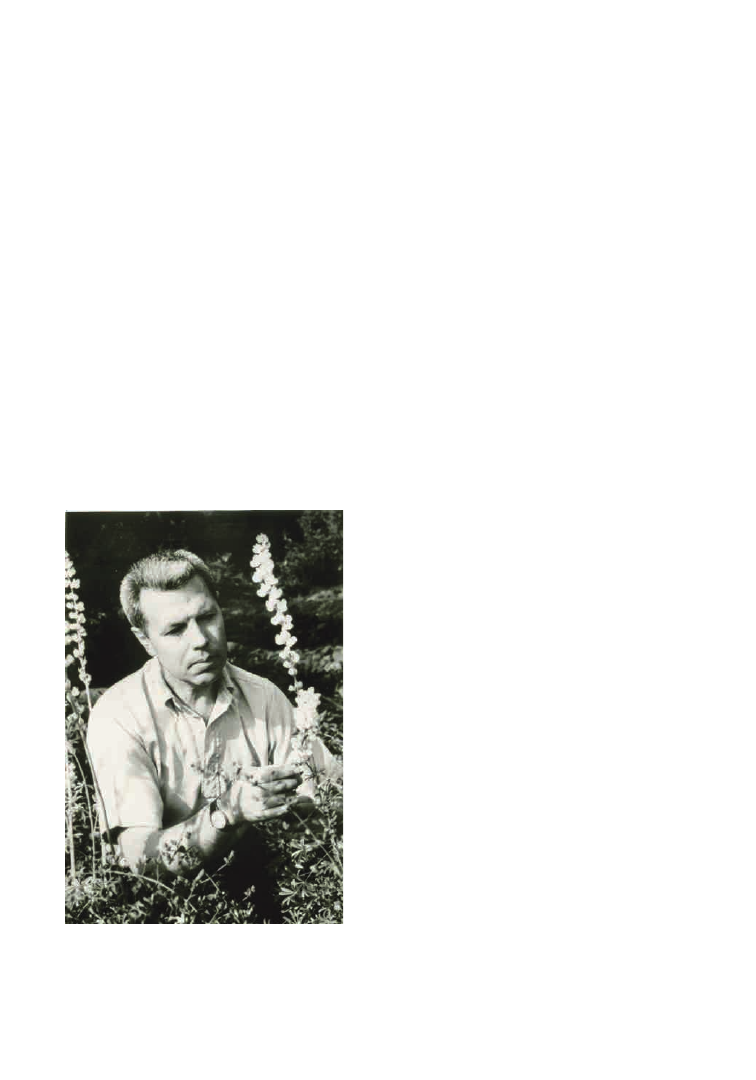

JOHN BARTRAM

John Bartram was born on 23 March 1699,

in Darby, Pennsylvania, a Quaker settlement

south of Philadelphia. His grandfather, also

John, moved to Pennsylvania in 1622, the

year Philadelphia was founded by William

Penn (Darlington, 1849). In 1708 Bartram

inherited his uncle’s farm in Darby, which was

fortuitous, as his father moved the rest of the

family to what was then the colony of Carolina

in 1711 and sold his land in Pennsylvania. His

father, William, was killed in an Indian attack

later that year in the first engagement of the

Tuscarora War (La Vere, 2013). In 1723 John

married his first wife, Mary Marris, and they

had two sons. Mary, as well as his older son,

died four years later. As noted above, Bartram

bought his first piece of the garden property

the following year (Berkeley and Berkeley,

1982). A year later, in September 1729, he

married his second wife, Ann Mendenhall;

they moved to Kingsessing and he began

enlarging the house. They had nine children,

two of whom are important for the garden.

William, and his twin sister Elizabeth, was 5

th

born and John was 8

th

(Darlington, 1849).

PSB 66 (1) 2020

20

From an early age John valued education,

although he only attended country-schools.

Nevertheless, he studied Latin and Greek

on his own, was inclined toward medicine,

and sought out men of good learning. He

was a founding member of the American

Philosophical Society, established in 1743, and

represented Botany, one the nine recognized

fields of knowledge. Bartram followed

Benjamin Franklin on the list of members,

and Franklin hoped Bartram would prepare a

comprehensive natural history of the colonies

(Ewan, 1968).

John’s occupation, though, was a farmer. He

extended his productive lands by draining

and reclaiming marshland along the river.

He rotated his crops and periodically planted

a fallow field with red clover. He fertilized

his fields with lime, ashes, and manure. As a

result, his crops of wheat, flax, oats, and maize

greatly outproduced that of his neighbors (de

Crevecoeur, 1782). His farming and interest

in medicine explain his love of botany and his

son’s observation that he would contemplate

the “beauty and harmony” of plants even as he

was plowing his fields or mowing his meadows

(Bartram, 1804). As a consequence, “He

was, perhaps, the first Anglo-American, who

conceived the idea of establishing a botanic

garden, for the reception and cultivation of

the various vegetables, natives of the country,

as well as of exotics, and of traveling for the

discovery and acquisition of them” (Bartram,

1804).

Physically and mentally, Bartram was well-

suited to his vocation. He was of above

average height and naturally industrious and

active. He was modest, good-natured, and

“an example of filial, conjugal, and parental

affection” (Bartram, 1804). Not surprisingly,

given his Quaker background, Benjamin

Smith Barton noted that Bartram “…was one

of the earliest espousers of the cause of the

Blacks, in Pennsylvania” (Bartram, 1804).

AN UNOFFICIAL NATIONAL

BOTANICAL GARDEN

Sometime around 1730 Bartram began his

travels, at his own expense, to collect local

plants and bring them back to his garden

for his own pleasure (Bartram, 1804; John

Bartram Association, 1907). In 1733 Peter

Collinson, a London merchant and avid

gardener, inquired, through Benjamin

Franklin, for a person to supply seeds and

cuttings of American plants for his garden.

A Quaker, and member of the Royal Society,

Figure 3. View of the “Seed House,” the

first greenhouse in the garden from Bartram’s

house. (author’s image)

PSB 66 (1) 2020

21

Collinson had been supplying books to

Franklin’s Library Company since 1731 and

knew both Franklin and the Company’s

secretary, Joseph Breintnall. Breintnall

recommended John Bartram, and the die was

cast (Wulf, 2009). Thus began a four-decade

long correspondence and plant exchange

between Collinson and Bartram (Berkeley and

Berkeley, 1992). Mainly through Collinson,

Bartram increased his circle of correspondents

and customers both in Europe and America.

Benjamin Smith Barton, the editor of William

Barton’s account of his father, mentions many

individuals from whom he had copies of

Bartram’s letters: Linnaeus, Gronovius, Sir

Hans Sloane, Catesby, Dillenius, Collinson,

Fothergill, George Edwards, and Philip Miller

in Europe, and Franklin, Dr. Alexander

Garden and Governor Cadwallader Colden

(see Sundberg, 2011 for the latter two) in

America (Bartram, 1804). Most of this

correspondence related to his distribution

of cuttings and seeds of American plants.

In 1752 alone, 29 boxes of plant materials

were shipped to Europe. Bartram’s list of

customers eventually grew to 144 merchants,

nurserymen, and peers in Europe and at least

33 friends and correspondents in America. In

addition to those mentioned above were: King

George III, the Prince of Wales, eight Dukes,

and nine Earls (Berkeley and Berkeley, 1982).

Bartram was beginning to build a business

selling American plants abroad, but he was

also providing a conduit for introducing plants

from other countries to America (Table 1).

While he was interested in introducing

plants into his garden, he also wrote to

Collinson about a number of “Introduced

Plants troublesome in Pennsylvania Pastures

and Fields”. Among these were: Hypericum

perforatum, “a very pernicious weed…

spreads over fields & spoils their pasturage”;

Leucanthemum vulgare, “a very destructive

weed in meadow & pasture ground choaking

ye grass & taking full possession of ye

ground”; and worst, Linaria vulgaris, “ye

stinking yellow linaria…ye most hurtful plant

in our pastures that can grow in our Northern

climate…the spade nor hoe can destroy it…

is now spread over great part of ye inhabited

parts of pensilvania[sic]” (Berkeley and

Berkley, 1982).

In 1735 (Meyer, 1977) or 1736 (Berkeley

and Berkeley, 1982), Bartram followed the

Schuylkill River to its source, collecting along

the way specifically for Collinson. The same

year he also traveled down the Delaware River

to the Great Cedar Swamp in New Jersey. In

1838 he made his first collecting trip south to

Maryland and Virginia. These local trips were

made in the fall, both because the harvest

had to be completed, but also because of the

variety of seeds he could collect. On 20 May

1741, he began his first trip to New York. By

now his connections were extensive and upon

his return home in the fall he began preparing

shipments for England, Holland, Sweden,

and the Jardin du Roi in Paris (Figure 4).

In June 1743, he wrote New York Governor

Cadwallader Colden that he would soon be

leaving for New York to begin his first extensive

collecting trip of a full year. Coulder and his

daughter, Jane, were well-known botanists in

New York (Sundberg, 2011).

On 3 July 1743, Bartram left Philadelphia to

meet Conrad Weiser, the Pennsylvania Indian

Agent, who would guide the trip and act as

interpreter. Weiser had to settle affairs with

the Indians at Onodago and could thus guide

Bartram all the way to Lake Ontario. They

traveled west to the Susquehanna River, then

followed it north to the mountains and on

into New York. This was a time of tension

on the frontier between the English colonists,

the French traders, the Iroqouis, and the

Delawares. Weiser had more than 10 years

PSB 66 (1) 2020

22

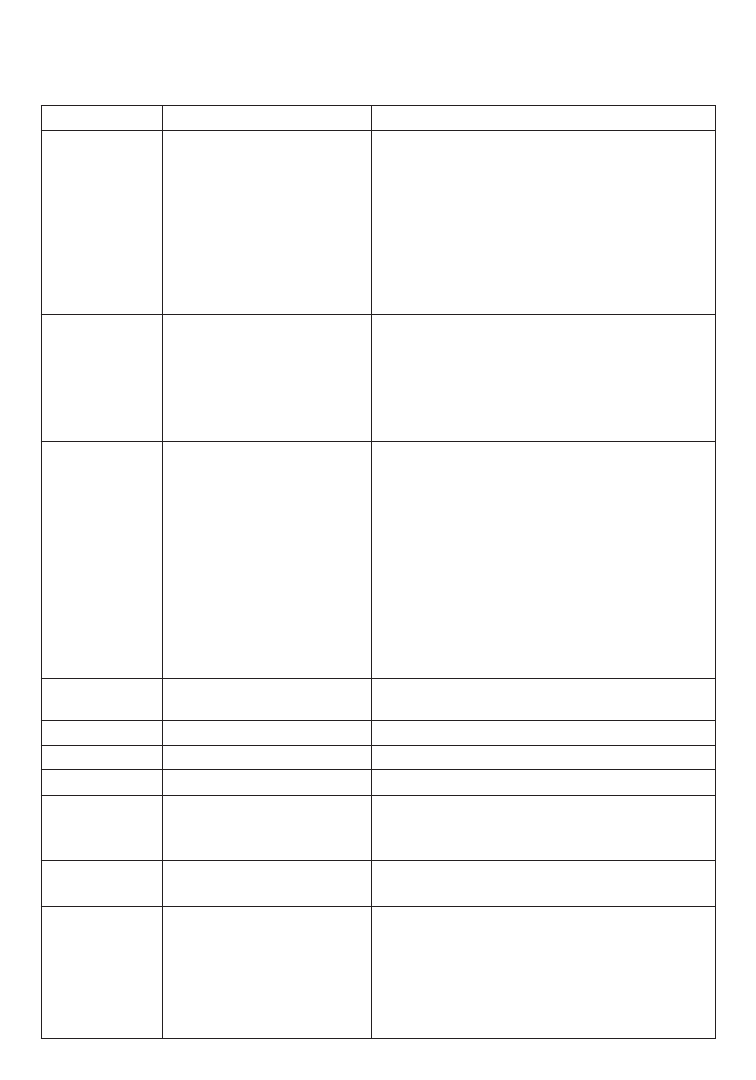

Scientific Name

Common Name

Scientific Name

Common Name

Acer platanoides

Norway Maple

Picea abies

Norway Spruce

Aesculus hippocastanum Horse Chestnut

Pinus sylvestris

Scots Pine

Ailanthus altissima

Tree-of-Heaven

Platanus orientalis

Oriental Plane

Arbutus unedo

Strawberry tree

Prunus laurocerasus Cherry Laurel

Buxus sempervirens

Boxwood

Pyracantha coccinea Firethorn

Colutea arborescens

Bladder Senna

Quercus robur

English Oak

Cornus mas

Cornelian Cherry

Sorbus aucuparia

European Mountain

Ash

Cytisus scoparius

Scotch Broom

Sorbus domestica

Service Tree

Hedera helix

English Ivy

Syringa persica

Persian Lilac

Larix decidua

European Larch

Syringa vugaris

Lilac

Laurus nobilis

Laurel

Thuja orientalis

Chinese Arborvitae

Melia azedarach

Chinaberry

Ulex europaeus

Gorse

Table 1. Some woody introductions to America that made their way through Bartram’s Garden.

of experience, which produced in him a very

different attitude about the country than that

described by Bartram. Bartram commented

on the soils and vegetation and the pleasant

views. On July 11, near Shamokin, he described

“an old Indian field of excellent soil, where

there had been a town, the principle footsteps

of which are peach-trees, plums and excellent

grapes.” He later casually mentions the conflict

between the Iroquois and neighboring tribes

and potential effect on settlers (Bartram,

1752). According to Merrell (1999), “The

same ‘Dismal Wilderness’ that temporarily

darkened even Bartram’s sunny disposition

in July 1743 almost killed Weiser in March

1737…an escape from Hell.” Coincidently,

about 10 years later (May 1754), and 150 miles

further west, George Washington, a colonel in

the Virginia militia, ignited the French and

Indian war at Fort Necessity, near today’s

Pittsburgh (Merrell, 1999). Bartram arrived

home on 19 August 1744, and eventually

published his observations in a short book

(Bartram, 1752; Berkeley and Berkeley, 1982).

Twelve years later, during the war, Bartram

again accompanied Weiser on a diplomatic

From Fry, 2002.

Herbs included: lilacs, tulips, narcissus, roses, lilies, crocuses, gladioli, iris, snapdragons,

cyclamens, poppies and carnations. Also Pomegranate. (From Middleton, 1925.)

PSB 66 (1) 2020

23

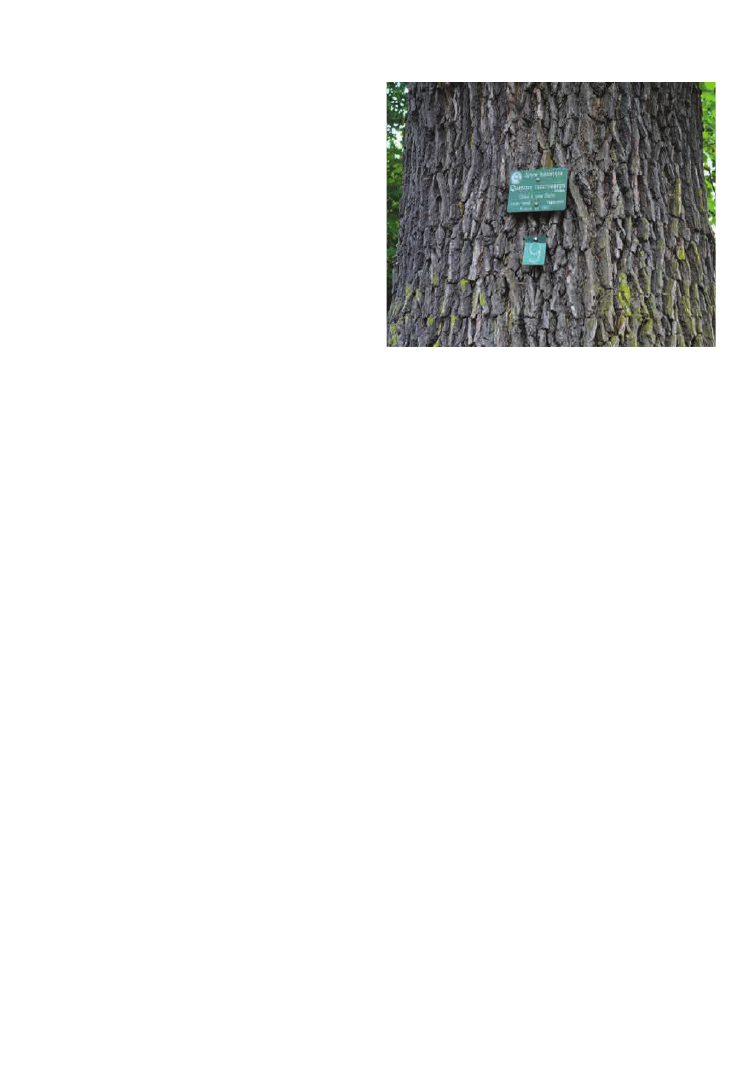

Figure 4. Quercus macrocarpa (Burr Oak)

growing in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris. (au-

thor’s image)

mission, but now wrote Collinson about

the “barbarous inhuman ungrateful natives

weekly murdering our back inhabitants”

(Berkeley and Berkeley, 1982).

Bartram had difficulty finding traveling

companions for his collecting expeditions but

solved that problem in 1753 when he took

his 14-year-old son, William, on a trip to the

Catskills. It was during this trip that they

spent two nights at Coldengham, New York,

at Governor Colden’s home. Unfortunately,

Colden was in the city, but his daughter, Jane,

showed the Bartrams her plant collections

and they talked botany (Berkeley and

Berkeley, 1982; Sundberg, 2011). Not only did

William assist his father on these trips, but he

continued collecting for the garden long after

his father’s death.

In 1760 Bartram set out on his first trip to

the Carolinas to visit his brother William,

who lived near Cape Fear, North Carolina,

and the botanist Dr. Alexander Garden

in Charlestown. The highlight of the trip,

however, was a visit with Governor Dobbs,

who had recently described a plant he called

“Fly Trap Sensitive” to Collinson. Bartram

was not able to collect the plant, but in early

summer of 1761 he asked his son, William,

who was in Carolina, to send some seeds

and roots of “ye pretty sensitives at A proper

season”. The following year Bartram informed

Collinson that he had included some of these

“sensitives” in his latest box of seeds and plants.

The shipment was captured by a French vessel,

and the plants rotted by the time they reached

London. Collinson replied that he would

like William to at least make a sketch of “the

sensitive” and send it to him. Bartram replied

that one of the plants he kept had died, but two

others survived in the garden. He said that in

some ways it resembled the sensitive briar “…

but this is quite smooth slender stalked & both

closet its leaves & gently prostrates: my little

“Tipitiwitchet sensitive” stimulates laughter

in all ye beholders…” (Berkeley and Berkeley,

1982, 1992) Collinson finally received

specimens in June 1763, and responded to

Bartram. “O, Botany, Delightfullest of all

Sciences… I have sent Linnaeus a Specimen

& one Leafe of Tipitiwitchet-Sensitive –

Only to Him, would I spare Such a Jewel …

Linnaeus will be In raptures at the Sight of

It…” (Berkeley and Berkeley, 1992). William

had already completed his drawing as a small

insert on his American Lotus plate (Figure 5).

William “related how he saw ‘the ludicrous

Dionea muscipula in the savannah of North

Carolina’ and, appropriately, records the

pioneer efforts of his father in communicating

the ‘wonderful plant’ to Europe” (Ewan, 1968).

Nevertheless, in September 1769, John Ellis

described the plant to Linnaeus, who named

it Dionea muscipula (Ellis), not Tipitiwichet

(Bartram), in 1770 (Ewan, 1968).

PSB 66 (1) 2020

24

Figure 5. Dionaea muscipula, Venus flytrap,

in lower left corner of William Bartram’s

American lotus, plate 21. (In: Ewan, J. 1968.

William Bartram Botanical and Zoological

Drawings, 1756-1788.

Philadelphia:

American Philosophical Society.)

In August 1765, John, having recently been

appointed “Botanist to his Majesty” by King

George III, left on his first trip to Georgia

and Florida, accompanied by William. It was

on this trip that they discovered Franklinia

(Figure 6) in southern Georgia, although the

discovery was not included in Bartram’s journal

other than “…this day we found several curious

shrubs…” (Bartram, 1942, p. 31). They made

no collection. William did collect it later on

his famous “Travels” and brought seeds back

to the garden in January 1777. It is well known

that Franklinia has not been found in the

wild since shortly after William’s collection.

This may not have surprised John. In 1763

he wrote Collinson that during his 30 years

collecting, he never found “one single species

in all ye times that I did not observe in my first

journey through ye same province but many

times I found that plant ye first that neither I

nor any person could find after which plants I

suppose was destroyed by ye cattle” (Berkeley

and Berkeley, 1992). Bartram was already

acknowledging human impact on the loss of

biodiversity.

John had already retired in 1771 and John Jr.

took over management of, and later inherited,

the garden and farm. Unfortunately, John Sr.

never saw Franklinia in flower because he died

22 September 1777 (Bartram, 1958; Berkeley

and Berkeley, 1982). According to Middleton

(1925) one of Bartram’s last concerns was that

the British Army, advancing from their win

at the Battle of Brandywine 11 days earlier,

would destroy the garden. But the British “as

a fitting tribute to the services of the simple-

minded scientist to their native land spared

the garden….”

In 1762 John compiled a list of 169 trees and

shrubs he knew he had growing in the garden,

But “…I have many plants that is so young that

thair[sic] proper Characters is not so visible as

to ascertain their Genus & many that is A quite

new Genus… (Berkeley and Berkeley, 1992, p.

555). The 1783 catalogue put out by John Jr.

and William listed 218 species available for

sale.

According to Fry (2002), John Jr. and William

probably shared a business relationship

with John Jr. handling the paperwork,

William the annual gathering, and both

cultivating, packing, and shipping specimens.

PSB 66 (1) 2020

25

Figure 6. Franklinia alatamaha specimen

southeast of Bartram’s house. (author’s im-

age)

International trade essentially stopped from

1775—before the outbreak of the American

Revolution—through 1779 when trade

with France picked up. The 1783 catalogue

corresponded with the Treaty of Paris in the

spring of that year (Bartram and Bartram,

1783).

Wulf (2009) suggests the garden played a

major role during the 1787 Constitutional

Convention in Philadelphia. Jefferson,

Madison, and Washington, among other

participants, were avid gardeners and had

purchased plants from the garden. Jefferson’s

first recorded visit was in 1783 (Fry, 2002) and

Washington first visited the garden on June

19, 1787, shortly after the Convention began.

By Friday, 13 July, “with the Convention on

the verge of collapse,” the Reverend Manasseh

Cutler, Madison and others decided on a trip

to Bartram’s garden the following day. Among

those on the Saturday excursion were: James

Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Alexander

Martin, Hugh Williamson, John Rutledge,

Caleb Strong, George Mason, Cutler, and two

native Philadelphians. (Franklin was ill and

unable to attend, although he was a frequent

visitor.) The garden was a metaphor for the

country and the delegates recognized many

plants from their home states, from as far

north as Vermont to as far south as South

Carolina, all growing together. Two days

later, the Convention passed the “Connecticut

Plan” with three of the garden visitors—

Martin, Williamson, and Strong—changing

their votes to create a majority. “It can only be

speculation that a three-hour walk on a cool

summer morning among the United States

of American’s most glorious trees and shrubs

influenced these men” (Wulf, 2009). Cutler

described the appearance of the garden as

such:

This is a very ancient garden, and the

collection is large indeed, but is made

principally from the Middle and Southern

States. It is finely situated, as it partakes

of every kind of soil, has a fine stream of

water, and an artificial pond, where he as

a good collection of aquatic plants. There

is no situation in which plants or trees are

found but that they may be propagated

here in one that is similar. But everything

is very badly arranged, for they are neither

placed ornamentally nor botanically, but

seem to be jumbled together in heaps….

(Cutler, 1888).

The variety of plants growing in the garden

made it particularly attractive for botany

courses from the University in Philadelphia.

Benjamin Smith Barton, the newly appointed

Professor of Medicine and Botany at the

University of Pennsylvania, included one

or more class field trips to the garden every

year (Sundberg, 2018). Table 2 summarizes

his extant notes on flowering dates associated

with 10 visits between 1785, when he was a

student, and 1816 (Barton; Sundberg, 2018).

PSB 66 (1) 2020

26

Visitors used to European gardens would

expect an orderly arrangement of specimens,

ornamentally or botanically, as suggested in

the above quote. However, the pragmatic

Bartram no doubt planted his specimens where

the aspect, protection, and soil would ensure

the best growth. His goal was to represent the

flora of every part of the country he visited—

or desired to visit. In a letter to Collinson

dated 11 November 1763, Bartram exclaimed:

“Oh! If I could but spend six months on the

Ohio, Mississippi, and Florida, in health I

believe I could find more curiosities than the

English, French and Spaniards have done in

six score years” (Berkeley and Berkeley, 1992).

THE COMMERCIAL YEARS

John Jr. probably constructed a new, larger

greenhouse around 1790. Certainly by 1807

there was more than one greenhouse and

the catalogue listed more than 75 native and

exotic greenhouse plants (Bartram, 1807; Fry,

2002). In total, 1143 species were available,

including 356 woody plants, 635 herbaceous

plants, 69 grasses, 20 palms and ferns, 46

mosses, and 17 fungi; some of these were, as

yet, new to science and had no formal names

(Bartram and Son, 1807; Anonymous, 1809).

Increasingly John Jr. concentrated on the

garden and plant nursery, eventually turning

the farm over to his son-in-law and oldest

daughter. John Bartram III, the next-to-

youngest child, assisted his father in the garden

until his early death in 1804. The youngest

son, James, was a medical student of Benjamin

Smith Barton who left Philadelphia for a two-

year voyage as a ship’s surgeon at about the

time of his brother’s death. Upon returning,

he partnered with his father at the garden and

was the “Son” in the 1807 catalogue. Daughter

Anne married Robert Carr in 1809, and James

married Mary Ann Joyce the following year.

The two husbands took over management of

the farm, and Anne and her uncle William

ran the garden, which was now advertising

its greenhouse plants for sale in local papers

(Fry, 1995). John Jr. died in 1812, and his will

divided the estate evenly between his three

surviving children. Although Anne’s husband,

Robert, was an infantry officer during the

war and was not discharged until 1815, their

inheritance included the garden (along with

“384 pots, boxes and tubs of plants” valued at

$250), the original house and outbuildings,

and the north meadow. These 32 acres are

approximately the extent of today’s Bartram’s

Garden Park (Fry, 2002). James died in April

1818 and William on July 22, 1823.

The Carrs enlarged the garden and brought it

to commercial success. The garden eventually

included orchards, greenhouses, cold frames,

and nursery beds (Fry, 2002). In 1832, William

Wynne, recently hired from England to be

Foreman at the garden, wrote an account of the

nurseries and gardens around Philadelphia in

the Gardener’s Magazine, London. Not only

was Bartram’s the oldest garden in the country,

but it had the best collection of American

plants in the United States with more than

2000 species. Many of the specimens are large

and prodigious seed producers, supplying an

export market throughout Europe, Asia, and

Africa. The tool house, the gardens, and the

seed house are all kept “in the best order.”

Later in the same volume, Alexander Gordon

(1832) noted there was an excellent collection

of cacti, including many undescribed species

from South America as well as houseplants

and fine fruit trees.

Five years later Gordon (1837) expanded his

description of the garden operation, giving

particular credit to Anne. “Mrs. Carr’s

botanical requirements place her in the

PSB 66 (1) 2020

27

Table 2. Notes on flowering by Benjamin Smith Barton at, or on the way to, Bartram’s Garden

Date

In Flower

Comments

June 13, 1785

Lobelia syphilitica

Galega virginica

Styrax grandifolium

Itea virginica

Oxalis

Sambucus

Viburnum

In the woods near Mr J. Bartrams Garden

On the rocky hill, near Grey’s Ferry, going to Bartram’s

Mr. W. Bartram says this plant is in its greatest perfec-

tion as far as he has seen about Cape Fear in North

Carolina.

In the garden.

In the woods near Bartram’s

In the woods near Bartram’s

In the woods near Bartram’s

April 15, 1791

Gauthoriza aprifolia Vinca

Palustris

Thuya, from Lake Ontario,

Sanguinaria Canadensis

Saxifraga Pennsylvanica

Houstonia caerulea

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

Between Grays Ferry and Bartrams

Between Grays Ferry and Bartrams

Sept 17, 1799

Sigesbeckia occidentalis

Cane [Arundinaria?] aovata,

Helenium autumnale, Franklin-

ia,

Tobacco

Lematula paceriofl

Heracleum sp.

Scrophularia marylandica

Rudbeckia laciniata

Mespilus arbutifolia

Nepeta cataria

Polygonium

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

In flower in Mr. Bartrams garden

found wild not far from his house, is not H. sylvicum

in same place not far from house

met a good deal during the walk

We found growing wild.

Wm does not think it is native

Wm does not think it is native

May 8, 1806

Aesculus

Delphinium

At Bartram’s

At Bartram’s

June 6, 1808

Roses

May 11, 1810

Delphinium

In open ground at Bartram’s

May 17, 1810

Arethusa ophioglossoides

One specimen at Bartram’s

Aug 14, 1813

Convallaria

W. Bartram assures me that he found on Cape-Fear, in

N Carolina, abundance the same that is common about

Philadelphia

Aug 18, 1813

Yucca gloriosa

In Bartram’s garden, open ground, fast getting into